On 22 June the so called Five Presidents’ report, authored by Jean-Claude Juncker, Donald Tusk, Jeroen Dijsselbloem, Mario Draghi, and Martin Schulz, was published, outlining plans for strengthening economic and monetary union. Iain Begg assesses what the report means for the future of the euro. He finds that while some of the proposals are well-judged and combine ambition with realism, others are too vague, and that there are still areas, such as the future role of the ECB, that deserve attention. He also notes the risk that some EU countries may lack an appetite for further governance changes and that the proposals may be challenging for the UK.

On 22 June the so called Five Presidents’ report, authored by Jean-Claude Juncker, Donald Tusk, Jeroen Dijsselbloem, Mario Draghi, and Martin Schulz, was published, outlining plans for strengthening economic and monetary union. Iain Begg assesses what the report means for the future of the euro. He finds that while some of the proposals are well-judged and combine ambition with realism, others are too vague, and that there are still areas, such as the future role of the ECB, that deserve attention. He also notes the risk that some EU countries may lack an appetite for further governance changes and that the proposals may be challenging for the UK.

Since the Greek crisis first erupted in the autumn of 2009 – yes, it is that long ago – the EU has put in place a range of new governance mechanisms designed to make economic and monetary union (EMU) more effective and resilient. Yet, by common consent, there is more to be done. The latest proposals come in the form of what is being called the Five Presidents’ report, made public on the 22nd of June 2015.

It contains updated plans for ‘Completing Europe’s economic and monetary union’ in three stages by 2025, with the aim of dealing with many of the flaws exposed by the crisis in the original design of EMU, and follows the Four Presidents’ report on achieving ‘Genuine economic and monetary union’ published in 2012. The four Presidents were those of the European Council, the European Commission, the European Central Bank and the Eurogroup, the last being the body which brings together the finance ministers of Eurozone countries. This time Martin Schulz, President of the European Parliament, has muscled his way on to the cover page as the fifth.

Two of the Five Presidents, Jean-Claude Juncker and Donald Tusk, Credit: European Council (CC-BY-SA-ND-NC-3.0)

While such plans are, on the whole, welcomed by the UK, keen to see a restoration of stability across the Channel, they are also a source of some anxiety. One of the lower profile themes on the UK’s renegotiation agenda is to make sure that new deals agreed by the Eurozone do not place the country at a disadvantage. It may lack the visibility of the debates around immigration and benefits, but could potentially be more disruptive and maybe even threatening to UK interests. In particular, the prospect of financial regulations inimical to the City of London has been a persistent concern.

The 2012 Four Presidents’ report proposed closer integration in four main areas. These were: banking union; closer integration of budgetary policies, including a possible additional budgetary capacity at Eurozone level and a common debt instrument (a limited form of Eurobond called Eurobills); better coordination of economic policies other than fiscal policy; and a strengthening of democratic legitimation and accountability – potentially bringing about at least a degree of political union.

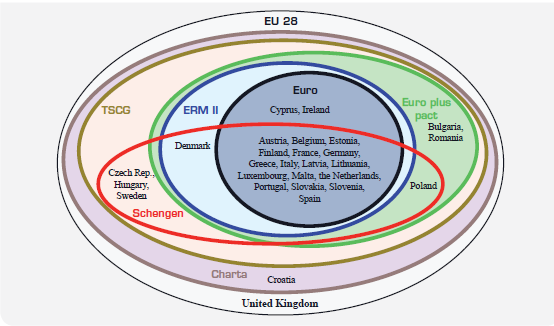

In the end, only the banking union dimension made much progress, first through the agreement of a new structure for prudential supervision of banks (the single supervisory mechanism, with the European Central Bank at the pinnacle of a network of national supervisors), and a common approach to resolving failing banks (the single resolution mechanism). Some of the Member States outside the Eurozone voluntarily agreed to participate in these initiatives, although it will be no surprise to readers that the UK was not among them.

The same broad headings remain in the new report, but some of the more contentious components have been dropped or toned-down in scope. There is no longer any mention of new fiscal capacities nor of debt mutualisation. Instead there is a more vague call to create a ‘fiscal stabilisation function’, the details of which will be worked out by an expert group to be set up in due course. Principles for fiscal stabilisation include avoiding a system that will result in permanent cross-border transfers – plainly intended to allay the concerns of the creditor countries – as well as ensuring compliance with fiscal rules and the common EU (NB: not just Eurozone) Fiscal framework. The discussion also makes clear that any new arrangements are not to be used for crisis management.

Two of the more eye-catching new proposals are intended to complete banking union. The first is to establish a common deposit insurance scheme to complement the protections offered to depositors by national agencies. This was one of the original ideas for banking union which failed to garner enough support after 2012, for the basic political economy reason that creditor countries saw it as potentially an open-ended commitment to bail out debtor countries – in other words a moral hazard risk. The new proposal suggests making the common scheme a form of reinsurance for national deposit insurance, providing top-down funding when the national scheme is in trouble, rather than an all-encompassing supranational one. It will be based on contributions from the banking sector, rather than public money, and is a sensible compromise solution that should make it easier to accept.

The second development will be what is called a ‘bridge financing mechanism’ as a backstop to the single resolution fund already agreed at the end of 2013. Critics had complained that the fund in question risked being too small and too slow to build up to its target size (it was to take ten years and thus not to be fully operational until 2025). There is a clear logic to making money available rapidly given the continuing precarity of many European banks.

If both these proposals make headway, the result would be a more integrated and resilient Eurozone banking system and would go a long way towards breaking the ‘doom-loop’ in which problems in the banking system cause problems for public finances (think of Ireland, Spain and Cyprus), or problems in public finances cause banking fragility (Greece). But agreement will be hard to reach for the same reasons as before, namely that creditor countries will fear that they will be put at risk, even though the plan is, ultimately, to raise money from the financial sector rather than tax-payers. Restoration of ‘normal’ bank lending is, nevertheless, vital to restore economic growth and to reduce the dangerously high levels of unemployment in many Member States.

The report also emphasises the importance of the Capital Markets Union which is at the top of the agenda of UK European Commissioner, Lord Hill. In other currency areas, such as the US dollar, private financial flows mitigate many of the consequences of an asymmetric shock affecting only certain regions, but cross-border flows of this sort have been more limited in the Eurozone, inhibiting an important adjustment mechanism. It is not a magic bullet, but a deepening of European capital markets should, in time, complement other mechanisms.

On fiscal policy, the Five Presidents are more circumspect than was the case in 2012. They reiterate the importance of fiscal discipline – referring to ‘responsible budgetary policies’. Apart from the suggested new approach to fiscal stabilisation, they call for the creation of a European Fiscal Board to act as an independent check on the conduct of fiscal policy. Many countries have already set up their own fiscal councils (the UK’s equivalent is the Office for Budget Responsibility – OBR), but they differ in their scope and influence. The OBR, for example, was given responsibility for official forecasts as well as examining the government’s fiscal plans, whereas (as an illustration) the Irish Fiscal Advisory Council is asked only to assess the government’s forecasts and budgetary plans.

The Five Presidents’ advocacy of this new Board is justified by the claim that it would ‘lead to better compliance with the common fiscal rules’ and would result in ‘stronger coordination of national fiscal policies’. It stops short, however, of saying that it would facilitate the setting of a common Eurozone fiscal stance, the absence of which is something that many critics of euro governance have bemoaned. Indeed, many leading economists have argued that a collective fiscal stimulus is precisely what the Eurozone needs today to boost economic growth, but that it cannot be achieved while decisions on fiscal positions are left to national authorities. A consequent danger is that the Five Presidents’ ideas will be seen (fairly or not, but it is often perceptions that matter as much as intent) as offering no way out of the prevailing austerity narrative.

There is also a hint that the new fiscal board should contribute to ‘informed public debate’. This would be welcome, but the new board will need to demonstrate its independence from, notably, the European Commission, if it is to become a distinct and credible voice. Two other institutional innovations discussed are a move towards common Eurozone representation in external fora, such as the International Monetary Fund, and a rather tentative floating of the idea of a Eurozone Treasury. The latter is bound to be highly contentious, even though the Five Presidents assert firmly that tax and spending decisions would continue to be taken at Member State level. A possible implication of a new Treasury is the need to appoint a Eurozone Finance Minister, but that is not examined in the report.

Over the last few years, the European Central Bank has greatly expanded its governance role, not only in the formal powers associated with banking union, but also in, for example, being one of the three institutions in the Troika overseeing countries subject to macroeconomic adjustment programmes. Some readers may, therefore, be surprised that, although one of the Presidents is Mario Draghi, the report makes no direct proposals about the future role of the ECB in economic governance. Some might say that is because the ECB has, on the whole, been decisive and effective so that it is best to leave well alone, but it is a dimension of completing EMU that others might think warrants examination.

A key challenge in completing monetary union will be to obtain public support for what are often politically difficult measures. Proposals by the Five Presidents around legitimation and accountability are similar to those set out in 2012, referring to the role of national parliaments and the European Parliament. The lack of progress on this component of a closer EMU is, itself, a source of dismay in several national capitals, although the Five Presidents note that the right (already agreed) to call European Commissioners to appear before national parliaments ‘should be exercised more systematically than at present’.

It is worth recalling that all these proposals will add to the array of governance changes already introduced since 2010. The fiscal compact, agreed despite David Cameron’s veto in 2011, and other reforms have established a more rigorous system for monitoring and coordinating national fiscal policies, while complementary governance innovations have been designed to curb damaging macroeconomic imbalances. The setting-up of the European Stability Mechanism (ESM) provided a permanent fund to be used to assist countries facing problems in funding their borrowing, and there is more systematic annual monitoring of national economic policy through the ‘semester’ process. Many of these new arrangements were introduced outside the European treaties, for example through separate treaties relating to the fiscal compact, bank resolution and the ESM. One other suggestion put forward by the Five Presidents is to integrate some of these into the EU legal framework, something that could well be seen as provocative in the UK if not handled with care.

For many national governments, the appetite for yet more change is limited, and this may make a number of them reluctant to countenance further extensive reforms. Brussels insiders seem to be agreed, however, that this could be the last chance to establish an enduring system for the governance of the euro. The Five Presidents are less ambitious than the Four and this is probably a wise choice. But they will need to deliver and thereby break the unfortunate propensity to announce wide-ranging initiatives at EU level, only for them subsequently to be watered-down to the much more limited reforms able to command a consensus. Wish the Five Presidents luck; they will need it.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/1K8ewys

_________________________________

Iain Begg – LSE, European Institute

Iain Begg – LSE, European Institute

Iain Begg is Professorial Research Fellow at the European Institute of the London School of Economics and Senior Fellow on the UK in a Changing Europe Initiative of the UK Economic and Social Research Council.